When a colleague asked if anyone had any stories of the development of computers in the 50’s and 60’s I had to own up to a family secret; my dad was one of the first geeks. He was invited to the first meeting of the British Computing Society in 1959 and, until his death in 1974, he remained close to the cutting edge of hardware and software development.

So, what do I know about the ‘early days’ ..?

Not many people realise that much of the pioneering work to make computers useful to business was carried out here in the UK and that, for a time, Britain was the world leader in developing hardware and software for commercial use. Most of us have heard of Bletchley Park, only a few miles from Northampton, and of how our need to crack German military codes led to the creation of the world’s first true computer there, but, after the war, the head-start provided by the Park’s code-breakers was largely lost due to the government decision to keep the invention a secret. That allowed the USA to take up the running, creating room-sized computers that mainly ended up in universities and in government departments. Then a British company called Lyons, famous mainly for their corner teashops, decided it needed a better way of keeping track of its payroll, and so its forward-looking directors decided that one of those new-fangled computer machines being produced in the States might just be the answer. Little did anyone know that a corner-shop business would end up spawning a new generation of computers and software specifically designed to help run businesses. From selling tea and cakes, Lyons moved into making computers, with the first one being called – naturally – Leo. Leo, and its descendants, gave a new impetus to computers in the UK and a new lease of life to geekdom in the UK. Which is where I come in …

mainly for their corner teashops, decided it needed a better way of keeping track of its payroll, and so its forward-looking directors decided that one of those new-fangled computer machines being produced in the States might just be the answer. Little did anyone know that a corner-shop business would end up spawning a new generation of computers and software specifically designed to help run businesses. From selling tea and cakes, Lyons moved into making computers, with the first one being called – naturally – Leo. Leo, and its descendants, gave a new impetus to computers in the UK and a new lease of life to geekdom in the UK. Which is where I come in …

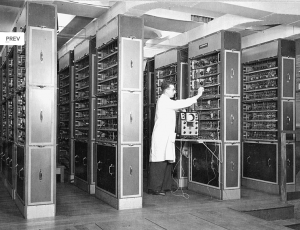

I was born in a semi in Kingston-upon-Thames. Here’s the inside of our house; just look at our TV!  I remember watching Andy Pandy and the Woodentops on it, and also ‘Listen with Mother’ on the radio. My Dad was a prototype geek, as you can probably tell from the photo, and after studying maths at University and learning Russian for his national service, he went on to work for Leo Computers, English Electric and ICL in the ‘50s and ‘60s, helping to develop the earliest business computer applications.

I remember watching Andy Pandy and the Woodentops on it, and also ‘Listen with Mother’ on the radio. My Dad was a prototype geek, as you can probably tell from the photo, and after studying maths at University and learning Russian for his national service, he went on to work for Leo Computers, English Electric and ICL in the ‘50s and ‘60s, helping to develop the earliest business computer applications.

Leo actually stood for Lyons Electric Office, and the first Leo computer was as big as two bus-shelters and relied on punched cards and card readers for its inputs. It had 7,000 valves and a memory of just … 2K! But it was a world-beater.

Leo soon had offices in Prague and Moscow, and, looking back through their archives, it must have been a very exciting field to be in. Here’s Ernest Kaye, one of the original design team sharing his memories about it in a BBC podcast. Read some more memories from the era here and here and here’s a fascinating video about Leo computers which shows what one ‘bit’ looked like then:

What comes across is that these people were real pioneers, reinventing computer technology to meet commercial needs. Ralph Land, talking in the video below gives a real flavour of the time, ‘It’s difficult to imagine now the sheer excitement of the group we worked in.….there was a constant buzz….you were doing something new almost every single day and that made it constantly exciting…you came home in the evening and thought about what had been done and it was quite exceptional’.

The Leo Computers Society website has a great collection of photos and evocative recordings of the sound of Leo, which was surprisingly noisy.

In 1963, Leo Computers merged with English Electric who opened a new computer factory in Kidsgrove near Stafford. In 1968, English Electric merged with ICL. And of course there were other companies working in the field across the world. In 1964 my dad represented Leo Computers on the programming standards committee ECMA alongside people from IBM, Siemens, and Ferranti. ECMA was an industry association started in 1961 to help standardise ICT systems, and it is still doing the same thing today. Sadly, my dad’s early death meant he missed out on the post 60’s explosion in the use of personal computers that came about as result of the invention of the microprocessor in the early ‘70s.

If this brief taste of the era inspires you to find out more, I can highly recommend the Sunday afternoon guided tour of The National Computing Museum at Bletchley Park where you can see a working replica of the code-breaking Colossus computer that was used there in 1943.

All fascinating stuff, but of course, I was just a young child while this was going on, and although I can remember my dad using words like Algol, Fortran and Cobol at the tea table, I could never make sense of it at the time. However, I can remember steam trains and cars without seat belts, and in 1963 we went on a package holiday to Yugoslavia, in a turbo-prop plane.  There was a sense of the world changing fast, of a new era coming in. So, what kind of world did the geeks inhabit?

There was a sense of the world changing fast, of a new era coming in. So, what kind of world did the geeks inhabit?

In the mid ‘60s we moved into a brand new housing estate in Cheshire so Dad could work at English Electric at Kidsgrove. The brave-new-world of the 1960’s not only had computers, it also embraced vivid colours and funky gadgets … I well remember living with wallpaper that required sunglasses to be able to look at it in the day, and design statements such as our orange perspex cube lamp and glass-topped table. Not to mention my dad suddenly taking to wearing patterned shirts and throwing out our large radiogram in favour of a set of the latest Quad hi-fi equipment, which he then put on our Danish teak wall shelves …

With Dad being into technology, we were one of the first families on the estate to have a colour TV in 1966 and I can remember friends coming round just to watch the test card!  We also watched the moon landing in 1969. I remember being surprised as a 9 year old that no-one had been to the moon before. Another trend was Saturday visits to the ‘Freezer Centre’ to buy frozen food for our new chest freezer. Packaged food like chocolate mousse in a plastic tub replaced homemade junket and we made fizzy drinks with a soda siphon on Sunday lunchtimes. We were the computer generation, and we were Modern!

We also watched the moon landing in 1969. I remember being surprised as a 9 year old that no-one had been to the moon before. Another trend was Saturday visits to the ‘Freezer Centre’ to buy frozen food for our new chest freezer. Packaged food like chocolate mousse in a plastic tub replaced homemade junket and we made fizzy drinks with a soda siphon on Sunday lunchtimes. We were the computer generation, and we were Modern!

Children’s clothes changed too during this decade and my sisters and I went from wearing knee-length handmade (sometimes hand-smocked) cotton dresses to short skirts made of synthetic fabrics such as crimpoline. In the last year of primary school, I was proud of owning a chain belt and ‘wet-look’ skirt, but really coveted my friend’s patent white boots!

In the 1980’s of course, we saw the miniaturization and the popularisation of computers. From being so big that they needed their own rooms they could suddenly sit on a desk-top, and from being the province of the geek, they became the toy for everyman. The price dropped and the power rose, exponentially. In came the Sinclair ZX and the Commodore 64, the BBC machine and the first Apple computer. The mouse appeared and the use of windows and icons, and all the things we take for granted today. My dad would have loved it if he’d had the chance to make the journey from Leo to the iPad, though I suspect he would have thought his generation lived through the most exciting time of all, when it was all new and the possibilities were just dawning. Perhaps he’d smile if he knew that I work in ICT and that I get excited by the possibilities …