Hassel and Rideout (2018) claim that a mismatch between expectations and reality constitutes a real risk for student dropout, suggesting such a mismatch means students are unprepared for what they really do experience at university. They refer to specific areas of mismatch as being: over-estimating contact time with staff, unrealistic beliefs re. staff availability, class size and workload (under-estimating optimal independent study hours). Their comment that students may not be prepared for a scenario “where students are taught by staff who are involved in a variety of other roles in addition to teaching” (p2) echoes a 1-2-1 tutorial comment where one of our cohort explained, “it’s not like school – we can’t just come and find you and know where you are.” Hassel and Rideout’s study (op cit) suggests students perceived this different structure as staff non-availability, where it may actually just be a different route to gaining access (for example, using email to make an appointment), so requires more planning and advanced notice of need. We need to be as explicit and clear as possible in explaining how lecturer and PAT availability ‘works’, since “in the absence of clear expectations regarding availability, participants try to make sense of their experiences by filling in the gaps with their subjective interpretations, which may or may not be reliably informed” (Yale, 2019, p6). This scenario runs the risk of repeating any previously negative educational patterns, and potentially reinforcing any prior disadvantage or perceived sense of deficit in self-identity as a learner. On our programme, we do clearly and explicitly share this explanation throughout welcome week, and ongoing (in person and on NILE). However, Yale’s data suggests that while students were familiar with the words indicating key elements of the uni experience eg ‘Independence’ – their understanding of what that meant did not match the reality and also led to uncertainty about when they should ask for help (op cit, p8).

Feedback timeframes on assessed work may also contribute to a shaking of expectations. Hassel and Rideout (2019, p3) cite the evidence of Crisp et al (2009) “that students may harbour unrealistic expectations about assessments, for example, supposing that lecturers will provide detailed feedback on drafts of their work and that staff will be able to return assessed work within a week.” Across the breadth of their experience, the expectations that students have before they start university may, “be pivotal in determining whether or not they deem …[the support and interaction they do receive] as appropriate” (Yale, 2019, p2).

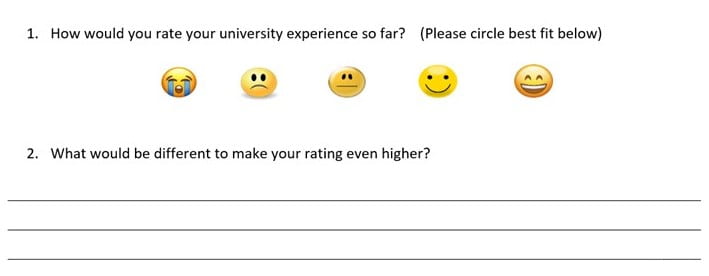

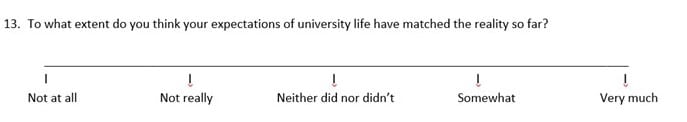

This project explicitly explored students’ expectations of university (and what had informed those expectations) at several points across the academic year. In week 1, students were asked what their expectations were and what had shaped those expectations. In week 4, students were asked to rate their university experience so far, and what might need to be different for them to rate that experience more highly. Then, in week 24, students were asked to what extent they felt their university experience so far had matched their expectations.

Week 1: STUDENTS’ EXPECTATIONS OF UNIVERSITY

Seven main themes emerged in what the students’ expectations were of university.

CHALLENGE:

A significant theme was the expectation of challenging workload and academic content. Students expected the experience to be “very full on with lots of assignments and reading to do”; the phrase “hard work” was frequently repeated – specifically, “studying, reading” and “challenging essays/assignments”. Work and workload was expected to bring “a lot of stress” and some students expected that they would “struggle with it”.

Some expressed their expectation of challenge with reference to the university experience as a whole: “It will be difficult”, “I expect the Uni experience to be challenging sometimes”. Sometimes, this was linked to the need for developing greater independence, eg “the journey will be tough, because adult life has just begun”. One student “expected university to be overwhelming” and particularly anticipated challenges in “settling in and making friends early on”. Other students also expected an element of challenge in peer interaction as part of the university experience, realising it would be “sometimes hard for everyone to get along in the house”.

FORMATIVE POSITIVES:

The arguably over-worn and pressure-creating expression that ‘University is the time of your life’, comes through as part of our students’ week 1 expectations. They were expecting to make “some of the best memories ever” from a scale of experience that would be, “life-changing, or at least some of the best 3 years of my life – education wise and socially”.

Socially, there was the frequently repeated expectation of “making lifelong friends“. This (and the pressure element of this theme) seems to correlate with the cohort’s Welcome week fears that they would not make friends or “click with people straight away” and fit in quickly enough. If you don’t meet this expectation are you really having the ‘university experience’, seemed to be the fear.

ACADEMIC GOAL ACHIEVEMENT:

The majority of comments relating to this theme, was the expectation to “get a degree (hopefully)” and to “graduate university“. Some goal achievement focused student expectations were more specific, in expecting “a high grade come graduation”; “a good degree”.

EMPLOYABILITY:

Many more expectations referred to employment outcomes than did to academic outcomes; which may have interesting implications for study motivation. I will return to study motivation in a subsequent blog, specifically drawing on the Korhonen et al (2019) article cited in previous blogs.

Several responses indicated the expectation that they would get a better job as a graduate – “a higher titled job“. One student stated most clearly, “I am not studying for no reason, I expect to get into a good job after this anyways.” For some, that ‘good job’ was a career in a particular field, and their expectation was that this degree was necessary to “get into the right field of work”.

Some employability-related expectations were more about improving students’ own abilities in future professional roles (so, in that sense, cross over with the later theme on self-development). Some have the expectation that going to university will support them to, “Improve my skills and abilities so I can give the best to the people I’ll work with“.

Other were not yet sure of their future career, and expected that the university experience would enable them to “leave with a clearer idea of a career path“, “open and create new avenues”; and that, specifically, “the work placement will guide me in what I want my future career to be like”.

SELF-DEVELOPMENT:

The frequent occurrence of this theme relates positively to study motivation. Numerous students expected that university would allow them to, “learn more about myself and how to live more independently”. They expected university to help them, “develop as a person and help me improve my skills and abilities”; to “become better than I am now“. This expectation was for the chance to “develop as an individual” and “gain more confidence”.

INCLUSIVE AND ENGAGING:

For some, the expectation was focused on a teaching and learning experience that would be supportive, respectful, inclusive and interesting. Through “guidance from tutors, and mentors in placements” they expected to “get the best support in my studies”. They “expected to feel engaged” with their course, and that “Staff will be as helpful as they can”, supporting “Interesting and engaging lectures/class sessions”. In term of Inclusion, the explanation of this explanation was – “Inclusive as in nobody is left out in and outside the classroom and that it is a safe environment to be a part of“. The over-arching expectation was for “an experience where I feel comfortable and able to produce my best work because I surround myself with the right people who can help me“.

DIFFERENT FROM BEFORE:

Several expectations linked to a potential default motivation for study, in having no particular view of what was expected, or being “unsure” of what to expect – but expressing their response as a view of what university would not be. University would be “different from anything I have experienced thus far“, and “better and more of an educational experience compared to my previous years”. Some students specifically “wanted to start university with no expectations”; although this stance may bring particular challenges when adopting a strategy to support transition.

What shaped students’ expectations? Where did they come from?

WORD OF MOUTH:

In most cases, student expectations had been influenced by the experiences of those known to them – usually family and friends. Often information was relatively contemporary: “mostly my brother – just graduated [a similar course] so we have had a lot of conversation about what I may expect from uni”; “Friends’ uni experience a few years ago gave me an insight”. Sometimes expectations came from, “older friends who have experienced university”, or from older relatives, such as parents and aunts: “My Auntie is the only one I know that went to uni and she said it was the best time of her whole life and an experience she’ll never forget”.

School or College: Sometimes this word of mouth was through teachers at school, by whom students had been “always told…that it [uni] was hard work”. Alternately, less personal messages from the “Education System” or “past experiences in Education” were also credited with shaping expectations of university.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND MOVIES:

These sources were both cited as informing expectations of university. “From different movies of time” through to “YouTube“; students were, “seeing people’s lives on social media and how they experienced university”, and this was shaping their own expectations.

Facebook groups were also cited as a social media route to clarifying expectations, although more interactively through participation in group discussions with other incoming students.

Active researching online led to students feeling ownership of their expectations and decisions, after “spending many days researching which university is best for me and seeing how my chosen university will support my needs”.

Some students seemed a lot less sure where their expectations had come from, and were unable to answer the question other than that they had “always had these expectations”.

MARKETING/Self-presentation from the university:

This was the second most frequently cited source of students’ expectations, with students referring to the university website, where “the university has shown me good pages”. Open days and taster days were repeated influences – “On taster days” and “at the open day, the way the uni presented itself allowed me to form those expectations”. There was awareness of the TEF, and this had increased expectations , as “UoN has TEF Gold so I expect very helpful tutors”.

In several instances, expectation-shaping input had only been very recent and was ongoing. Expectations stemmed “from the Welcome and Induction week” and students’ first-hand experiences so far: “My limited amount of time here and the first impression I got from the staff members here, before and after actually starting university”.

WEEK 4:

26 students participated in the questionnaire, and the average student experience rating was 1.3 (where the Likert scale responses were counted as equivalent to -2, -1, 0, +1, +2). Of these 26 students, 12 gave the highest possible rating (which was the mode response). The median rating was 1. Only 1 rating was negative.

A 5-point scale was insufficient for the degrees of variation some students wanted to express, so several adapted the scale to indicate a .5 response between faces/scale points and their responses were recorded accordingly.

For some students who rated the experience so far as a ‘1’, comments for what would increase their experiencing rating (like “being able to have more lectures” and “being able to have more one on one time with my lecturers”) may indicate some mismatch between expectations and experiences akin to those cited at the start of this blog post.

For some students who rated the experience so far as a ‘1’, an increased rating seemed to be more a matter of time; with the view that they would have an increasingly positive experience as they settled in. Then they would have “actually gotten used to everything” and got to “know the area better to feel more ‘at home’.” This comment about knowing the area better came from a student living in halls at the old Broughton Road campus. It was clear in these responses and in 1-2-1 tutorials that students living in halls there wished they “live[d] closer to the university” and had more around them.

Staying with students whose experience rating was ‘1’, there was still anxiety “about writing assignments” and the quantity of work. One student said their experience would be more positive if they were “not so alone” (which was followed up in 1-2-1).

The loneliness apparent in the previous explanation was also seen in (the small number of) experience ratings that were only marginally positive, neutral and negative. “The socialising experience, and still finding it quite difficult to settle in” was making the overall university experience barely positive for one student. Although another student who was “struggling with home sickness” said they “just need more time to settle in” whilst “trying to get used to the new course and assignments”.

The student who rated their experience so far at the lowest point on the scale, explained that what they needed to have a more positive experience was, “more interactions, my university experience would be better if I had a better understanding of my course and how I could achieve the grades I want.” Further responses from this student in the same questionnaire suggest that they hold themselves responsible for engaging in insufficient interactions – they think they “could engage more with the course” and “in lectures”. They may also be referring to peer interactions, as this was the student whose expectations in week 1 were that they would struggle with peer interactions and making friends.

There is an interesting balance between students’ week 1 expectations and the nature of their explanations for what might make their university experience more positive in week 4. For example, the highly achieving student whose week 1 expectations were for interesting, challenging and engaging lectures/sessions and assignments, at week 4 felt that, “some of the sessions have been slightly repetitive from my A’ levels, although there’s not much to be done about this.” There are issues here with a mismatch of expectations vs reality, but also an apparent lack of empowerment to change the situation. There are also issues, of course, in that we would want every student to feel appropriately challenged yet our students enter the programme with a very diverse range and level of prior subject knowledge and academic skills.

WEEK 24:

In week 24, two-thirds of the cohort (n=20) completed a far more quantitative style of questionnaire than those employed previously. I will refer to this as the Continuation, Achievement and Progression (CAP) questionnaire. The rationale was to gather quantifiable and anonymous data in this stage of the project, to identify any overall shift in themes that might be more openly expressed through an anonymous approach. The plan was to make this stage one and for stage two to be an extended focus group with student volunteers, during which the qualitative behind the quantitative might be explored. Unfortunately, stage two was due to take place after lockdown set in, and so the COVID-19 context prevented this data enrichment and participant clarification.

Of the 20 participants in the CAP questionnaire, 13 indicated that (to some degree) the reality of their university experience had matched their expectations. 7 of those participants gave the maximum possible response. There was a correlation between students who stated their experience of university “very much” matched their expectations and those who were “extremely satisfied” with the course content. This relationship did not work both ways though, in that 2 students who were extremely satisfied with the course content stated their reality of university matched their expectations “not really” or “not at all”.

If we believe the claims of Hassel and Rideout (2018), that a mismatch between expectations and reality constitutes a real risk for student dropout – 35% of students (albeit from a small sample) not perceiving a match (neutral or negative response) between their university expectations and reality seems a proportion that should cause some concern.

The CAP questionnaire was completed in early March and will have a blog post all to itself very soon.

Crisp, G., Palmer, E., Turnbull, D., Netelbeck, T., and Ward, L. (2009). First year student expectations: results from a university-wide student survey. J. Univ.Teach. Learn. Pract. 6:2009.

Hassel, S. and Ridout, N. (2018) ‘An investigation of first year students’ and lecturers’ expectations of university education’, Frontiers in Psychology, vol.8 p2218

Yale. A (2019): ‘Quality matters: an in-depth exploration of the student–personal tutor relationship in higher education from the student perspective’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/0309877X.2019.1596235

I find this aspect really fascinating. I find through discussions that students prior experiences of education are quite diverse, but those educated in England seem to have been coached through each assignment, and report having been allowed many re-writes of assessed coursework over several weeks before it was officially submitted. Many speak of their teachers having two sets of drawers, one being the official drawer for work ready to be sent off or inspected, and the others being for work still in progress. The lesson would begin with the essays still in progress being taken out of the drawers and distributed to the class, whilst the few deemed as having completed theirs would be given alternative work until the rest caught up. The returned essays had been read and were covered in improvement suggestions and corrections for the pupils to address in the class. The impression I get is that other than the pupils who do the essay well quite quickly, all the teaching the others got was ongoing coaching spanning several weeks for each assignment.

I had a student say to me a few years ago, that he FE College was loads better than uni because they had given her loads of support with her work, “whereas here I get nothing unless I come and ask for it”. On quizzing her further, the picture she painted was that all the FE lessons were assignment-focused, but more than that they were when the students actually did their assignments. The teacher could be called over at any time to help or advise. She assured me that every session after the first few had been ‘doing the next assignment’. The college was highly regarded and got their students good grades. Since then, I have asked many students about such things and most (but far from all) have described what I would call, almost continuous coaching, rather than teaching, or an education. Little wonder that university work and sessions is such a shock to many of them.

I have had interesting discussions about who actually got their wonderful grades, them nor their teachers, and their attitude is interesting. On the one hand, they strongly feel ownership over their grades, and also regard the grades as having been achieved through their hard work; it is the weeks of coached and guided assignment construction that they regard as being their hard work, and part of that is that they did fond it hard to do week after week, but they felt proud of the finished product. When I tease them and put it to them that it was the teacher who got the grade and deserved the qualification rather than them, because they’d just written what they were told to, they appreciate the work the teacher put in, but still say something like “but it was still us that actually did the work”. Conversely, they tend to express that it is the teacher’s fault if they don’t get good grades, not their lack of hard work. They feel that if the teacher had told them better stuff to write, or had given them better comments and guidance, they could have done better and got higher grades. They see the level of work they put in as being the same as when they got good grades, so feel they deserved equally good grades, and so blame the teacher for their lower grades, but regard their higher grades as being their own achievement. Taking this into account, when asked what makes a good teacher, a lot of the seminar respond by saying that good teachers are the ones who get you the best grades, which is kind of admitting that their good grades belong to their teachers as well as their bad grades. If challenged they will qualify their answer by saying the the best teachers are the ones that get you to do the best work, and by saying that they take back ownership of their better grades.

When I’ve asked students what they expected university to be like, they normally describe a super-high quality version of school or college in which all the teachers are like the very best ones they had at school/college and will get them the very best of grades, every time. They talk of being amazed that there are not lessons/lectures all day long. They seem to expect that teaching will be either just like at school/college but more intense, or that we will be like what they regard as the very best teachers at school/college – i.e. Super-Coaches: The concept of individual learning and preparatory research or reading in advance of a ‘lesson’ is therefore quite alien to many of them.

When I ask them (often at graduation) what they first thought about the lecturers when they had arrived as new students, they laugh and say things like “Where on earth did they find these people?” Further probing reveals that they have usually never met anyone who is anything like any of us even though we are quite different to each other. Basically, many have never met an intellectual, and academic, or even a professional outside of a professional environment (e.g. the doctor, the dentist, their teachers), and a great many have never met a truly middle class person before other than in a professional capacity. When I asked about social class one year a group described the Working Class as being people who sponge on benefits and either never or only rarely work; the Middle Class as being people who do low paid work but have a proper regular job (such as the dinner ladies at school); and Upper Class people were seen as professionals such as School Teachers. At first I was stunned by that and thought them to be stupid or thick, but eventually after reflecting on it I came to realise that they were trying their very best to make sense of terms that were unknown to them, or at least ones about which they’d never given thought or had conversations, and also that those three strata of citizens were the extent of their personally experienced social world . We seemed to them to be the weirdest of folk because we didn’t fit into any previously experienced group of people. They also expected us to “be like school teachers but suited and booted” “Like school teachers but more so”.

The great peculiarity to me though, is that when we arrange tutorial sessions, and the PT ‘co-working together’ sessions, they have no interest in attending them. Likewise, attendance is very poor at normal timetabled sessions designed around the coming assignment as a workshop than at what they now call “proper lectures”. They say such contradictory things like, we want more interactive stuff and discussions rather than ‘just’ a powerpoint, but then ask if it’s going to be a proper session this week with slides or just a chat “cause if it’s just going to be a chat, could I miss it cause I’ve got like loads of other work to do?”

Another thing I’ve noticed in my discussions with students, is that we don’t always interpret the words they say in the way they mean them. So, for instance, saying that as session is irrelevant (and I was told a few years ago that all our sessions are utterly irrelevant and not worth attending) means to us that they don’t see the importance of the topics or they don’t grasp how important the topics are to their future careers; but that is not what they mean. They mean, if it isn’t clearly and directly related to the next assignment their is no point in them attending because all they really want is to be told what to write in the essay and how to write it. With some logic, they say “The content might well be important to me once I am a teacher, but unless I get a good grade (by which they mean and sometimes even state: ‘unless you get me a good grade’) I won’t ever be a teacher so it won’t matter, so it is irrelevant.”

Because of all this, a while back, I altered my modules and their assignments and sessions so that they are as inter-dependent as possible. I came to the conclusion that every session must to be directly, not just relevant to, but needed for the assignment. However, I was determined that in doing so I was not going to reduce the level or activities to coaching for the assignments. I made them more responsible for their own learning, especially at levels 5 & 6. Uni policy sometimes interferes though; for instance: On one module they research a different behaviour in relation to education each week, and they used to then pick twelve to write about in the assignment, but the uni forced me to reduce the word count and so they now only write about eight.

I feel I could go on and on, but time has caught me and I must leave it at that, but I hope this is interesting and or helpful.

Thanks, Neil – gosh, this is a blog in its own right! It is interesting to hear you recount your conversations with students on your programme. I definitely hear what you say about the PT co-working scenario. I found that starting the new cohort with the understanding that we would have 1-2-1 tutorials (between me and every student) in the first and second half of term one was essential – like establishing that as the norm. I did try one co-working opportunity and, as you say, not a single student across 3 potential hours. Thanks for your thoughts!