In one of my earlier posts, I referred to the concept of ‘wobble week’ (Morgan, 2019); a point in time (between week 3-6) where first year students might be more likely to wobble in their commitment to staying at university. If any readers post-date the 1970’s and are unfamiliar with the image above; the catchphrase of the Weebles (popular toy – more modern Santa version shown above) was, “Weebles wobble but they don’t fall down”. Similarly, we would expect most humans to wobble in their endeavours at some points, and we would hope they would be able to re-stabilise and recover from that wobble ie not fall down (or in this context, not drop out).

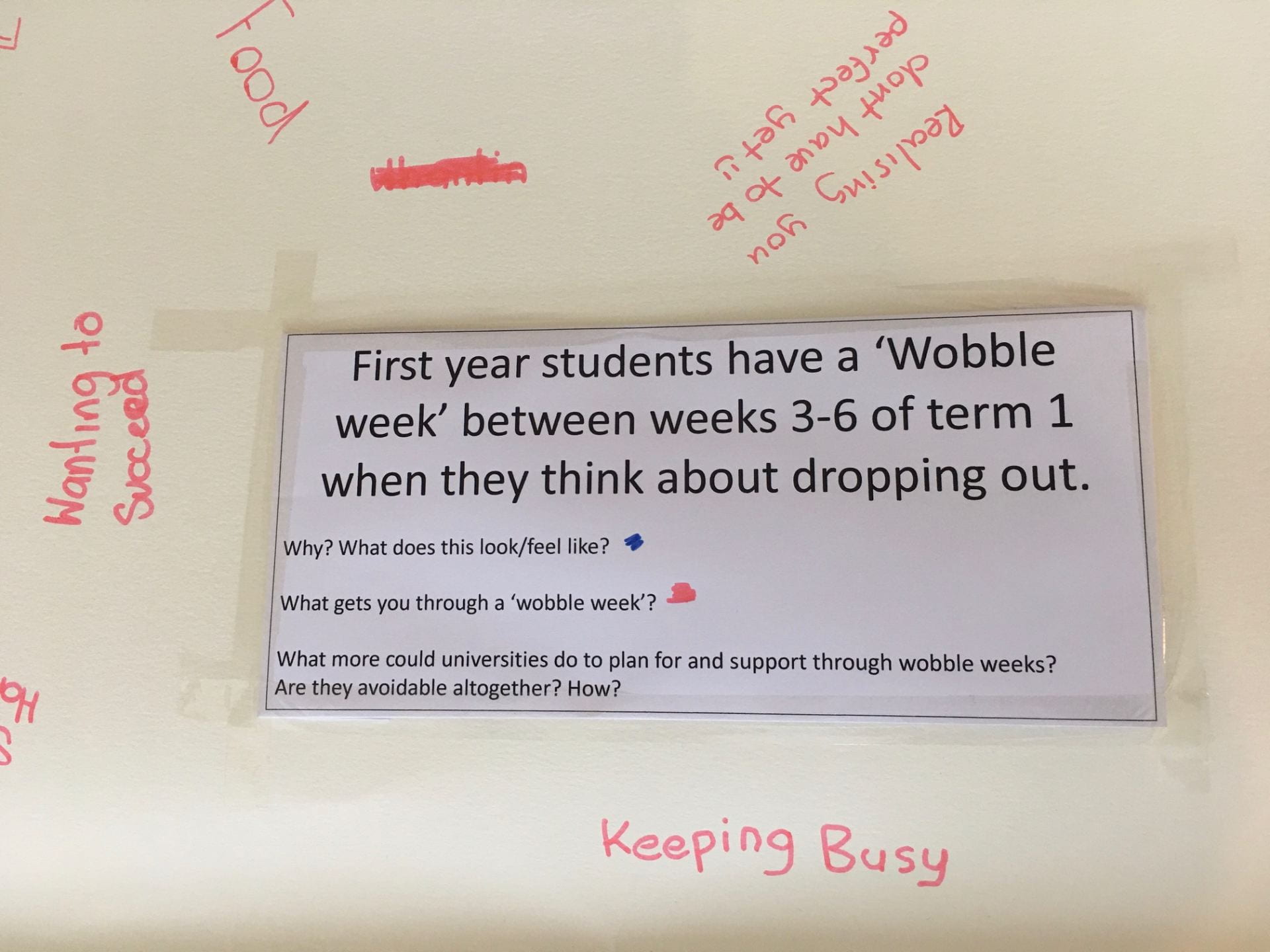

In our Week 11 group discussions, in addition to the Diamond 9 sort (see January blog) small groups were asked to consider and discuss ‘wobble weeks’ – both the earlier potential wobble point (around term one half term) and also the potential wobble over the winter break. The timing of this discussion was intentional, since the winter break was approaching and students were able to look back on how they might have felt at the first half term wobble point and potentially apply it to the upcoming winter wobble point; alongside a conscious and peer-supported consideration of what might get a person through (previously and moving forwards).

Discussion prompts were as follows:

In considering why a first year student might wobble around that first half term point, I’d like to refer back to some of the themes emergent in the students’ hopes, fears and challenges (discussed in the blog post immediately prior to this one). The need to develop practical organisational skills (such as managing their own time and learning), well-being (including mental health) and finance are themes that emerged in that previous discussion that re-appear in this wobble context. I am also very influenced by Korhonen et al (2019) and their exploration of the multidimensional nature of student engagement – particularly in their identification of significant factors intertwined with student engagement. From Korhonen et al (op cit) are drawn additional themes relating to motivation (including relevance of study); Interactions in the study-related community and academic experiences in the programme.

The most reiterated and emphasised responses to why a first year student might wobble during weeks 3-6 related overwhelmingly to an insufficiency of relevant practical organisational skills and achieving balance between competing pressures . For some students this looked like a “busy home life” and “family commitments”, and for others it was balancing across “not having enough time – working, assignments, family, social”, with this being experienced for those who might wobble as “overwhelming” “pressure”. The impact of well-being concerns came through also, with the suggestion that being “homesick” might cause a person to wonder if they should stay at uni, and that more “emotional support” was available at home. Finance also appears as a possible wobble trigger, if students are “worried about money – student finance = Hell!!”. In addition to the themes emergent re. hopes, fears and toughest challenges; discussing potential wobbles in wanting to stay at uni brought out a new theme at this point – motivation for study. This was the point in time students might ask themselves, “am I committed enough? Won’t succeed so no point continuing”, questioning their ability to achieve; or (“am I doing the right thing”) even whether the course and university experience was right for them and would help them achieve their goals.

Korhonen et al (2019, p4) cite the findings of Korhonen and Rautopuro (2012), that “expectation-driven motivation and default motivation predict problems in adapting to one’s program and motivating oneself to study.” They also suggest that, “problems in self-regulation and management of one’s own learning” (op cit) are indicative of disengagement and slower progression. We can see that these indicators may be recognisable in this group discussion data.

When considering what might get a first year student through this first half term wobble week, some suggestions seemed healthier than others. I was reminded of teaching previous students on a different programme about the concept of ‘Phase-Adequate Engagment’ as part of a Transitions module. Dietrich et al (2012) define the concept as, ““intentionally engaging in behavior that is appropriate to meeting the demands posed by the transition situation at hand” (p1575). They outline the differences between assimilative and accommodative coping and suggest a balance between these two strategies may best lead to adaptive development. In the former strategy, if a student felt their current situation was not what they wanted or had expected, they would work to change their situation so the mismatch was reduced. In the latter strategy, and accommodative approach would see the student adjust their goals or expectations to reduce the mismatch. I found it interesting that some of the behaviours I had deemed ‘less healthy’ as a response to this wobble week, constituted more of an avoidance of considering any mismatch rather than engaging in either assimilative or adaptive coping… they did not yet seem to have reached that point in the process. These were suggestions such as turning to “alcohol” or “food”, “keeping busy” and finding “distraction” from the concerns that might cause a wobble.

It was even more interesting that by the time the students’ consideration had moved to potential wobbles at point of the winter break, those types of suggestions for coping were absent; perhaps suggesting that by week 11 (when these discussions took place) students had now reached the point of engaging in coping strategies. It may be noteable that we had fewer wobbles on the programme (where students mentioned potentially leaving the course) from after week 11, than before this point. It would be interesting to consider whether a supported teaching and learning experience in the early weeks, explicitly exploring phase-adequate engagement and coping strategies, would support students to begin identifying and deploying their own coping strategies sooner and consequently, fall down less should they wobble. Drawing on the same Transitions module mentioned before, I would be inclined to structure such a teaching and learning experience around Schlossberg’s (2013) ‘Roles, Relationships, Routines and Assumptions’ as an accessible way to start considering where initial challenges for each individual student might be most located and best supported.

In addition to arguably less healthy suggestions as to what might get a first year student through that first wobble week, were supports we have seen drawn upon when considering hopes, fears and toughest challenges. These included drawing on support from outside university (“family”) and from within university. Within university support was seen as relevant and useful at this point, from “Personal Tutor”, “Residential life” and “housemates”, as well as “the new friends you’ve made – interest connections”. Several comments related to consciously staying positive and “realising that you don’t have to be perfect yet :-)” as well as recognising how far they have come and what they have achieved already as evidence that they can deal with this wobble too: “I am here now and might as well deal with it! I have come too far!” There were also suggestions to focus on how staying at uni was necessary to achieve their goals, such that they were “wanting to succeed”. These latter comments tie in with elements of what Korhonen et al (2019) saw as motivations for study that were positive indicators for continuation and success (motivation types of personal intellectual development and careerism-materialism – uni process as a more functional tool).

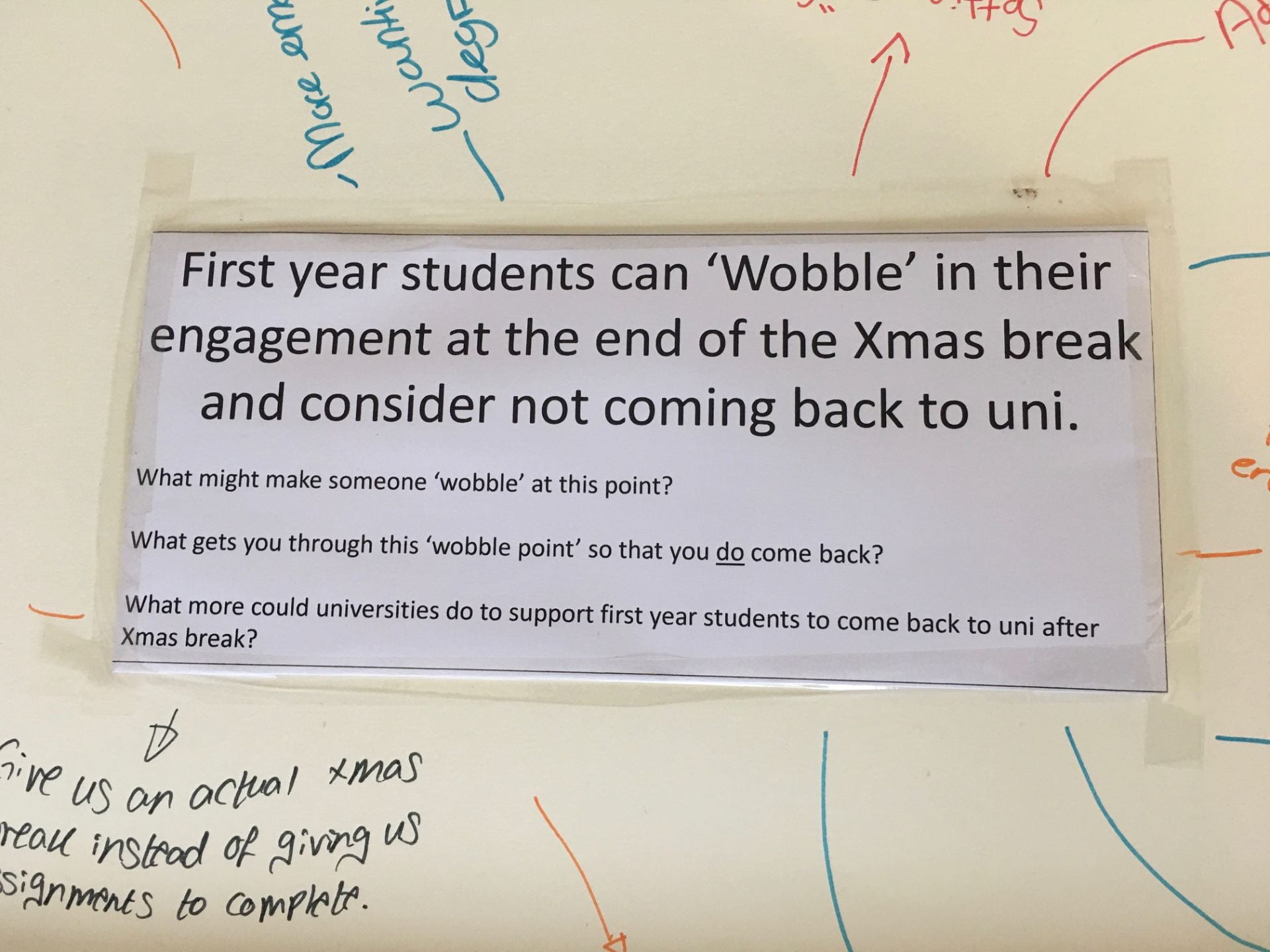

Moving on to what might cause a wobble over the winter break, the following prompt was used:

Interestingly, in comparison to wobble causes for the half term week, at this point in their studies triggers relating to an insufficiency of relevant practical organisational skills and achieving balance between competing pressures were far fewer. “Family commitments” still presented a relevant challenge, as did “work [that] probably got overwhelming”. Triggers relating to motivation for study remained, but again, were fewer. There was the suggestion that a first year student might have “wanted a trial period up until Christmas” and that it had been their intention from the start to see how they found the first term and then decide whether or not to commit. Then, once home, they “may decide that they don’t want to come back.” Well-being remains a consistent potential trigger, with the focus within that theme at this point being very much on “home sickness”, “missing home” and getting “more emotional support at home”. Finance has not disappeared as a potential trigger.

New considerations emerge at this point vs wobble triggers at the first half term. Interactions in the study-related community could now trigger a wobble. It could be a student is “not feeling comfortable” and they may have “issues in Halls”. By this point in the term, students have received their first assessment grades and are well in to the assessment process, such that academic experiences on the programme may now become a trigger for a wobble, if “assessment marks” are not what they had hoped for. Korhonen et al (2019) found associations between intention to drop out and “students’ self-regulation skills, interactions in the study-related communities and academic experiences in their program” (p4).

Finally, as can be seen in the bottom left of the image above, one of the most reiterated suggestions for what more the university could do to support students to return after the winter break, was to “give us an actual Xmas break instead of giving us assignments to complete” with “no assessments due first week back”. I think there are potentially two key issues at play here: the first comment is directly linked to a need to improve students’ practical organisational skills; since effective time management would allow a student to complete all their early January assignments prior to mid-December. The assessment schedule for the whole academic year is issued in WIW. The comment about assessments being due in the first week back could seem to echo that need, but actually may be more about needing to re-connect with the university and their uni networks in order to support that re-transition. It is possible that an assessment deadline focus in the first week back might distract from that re-anchoring. In this 2019-20 academic year, the block one modules ran until the end of week two term two, making assessments in those first two weeks very likely. However, in the 2020-21 academic calendar, teaching for the first block modules concludes just before the winter break, making this issue avoidable. We will definitely be taking these comments into account when planning our assessment schedule for the programme.

Dietrich, J., Parker, P. and Salmela-Aro, K. (2012) ‘Phase-adequate engagement at the post school Transition’, Developmental Psychology 48(6) pp1575-1593

Korhonen, V., Mattsson, M., Inkinen, M. and Toom, A. (2019) ‘Understanding the multidimensional nature of Student Engagement during the first year of Higher Education’, Frontiers in Psychology, 10: 1056 pp1-15

Korhonen, V., and Rautopuro, J. (2012). “Hitaasti mutta epävarmasti (Slowly but uncertainly),” in Opiskelijat Korkeakoulutuksen Näyttämöillä, eds V. Korhonen and M. Makinen (Tampere: University of Tampere), 87–112.

Morgan, M. (2019) Presentation to SEDA conference, 15th November 2019.

Schlossberg, N. (2013) ‘Even happy transitions can be challenging’, Sarasota Herald Tribune. https://www.transitionsthroughlife.com/about/articles-interviews/ [Accessed September 2009]

Rachel raises a number of important issues here.

1. I have never understood the concept of a welcome ‘week’. Feeling at ease at university and finding your ‘place’ in a new environment with new surroundings and people takes time. Going to university is also about self-discovery and often I think the first year or two are spent figuring out who you are and what you really want to do. So, the whole concept of ‘welcome’ and ‘induction’ needs to be thought of as a process which lasts months or years, not weeks.

2. I also think Rachel’s findings should be considered alongside the proposed semesterised timetable which has a ‘timetabled support’ week during week 8. If the sources cited above are correct, then this is too late. What should be done about this?

Some really interesting and important considerations have been raised in this post and I agree with Julian’s highlighting of the ongoing and more nebulous concepts of ‘welcome’ and ‘induction’.

In some ways it reminds me of the somewhat arrogant interpretation of ‘inclusion’ that suggests WE (the institution) know what will make YOU (the individual) fit in and feel ‘included’. These concepts are quite individual, subjective and existential and thus often internalised and not evident, visible or easily audited. There are links also to the ‘Sophomore slump’ whereby the novelty and relative freedom of the first year experience is matched by the gloomy sense of increased personal responsibility and drive in year two.

I found the ‘wobble week’ analysis very interesting since we do not take account of that in our assessments and teaching; indeed, setting online work during half-term week is actually encouraging disengagement. The usual patterns in truancy and/or attendance falling is that once an official ‘break’ is permitted, students may not come back to the timetabled sessions afterwards since the habit of attending has been broken and indeed broken by official sanction. I wonder if the terms are too long in that students think it won’t matte if they miss a week here and there, for half-term or booked holidays but then reach April and realise that the academic year is over. Why not three terms which are shorter and more intensive? Perhaps the semesters could address that, if intensive teaching times are built into the two longer semesters. I do think WW is of value; that is when they first meet one another and us and we make the first vital connections.

As a truantist, I can confirm you are correct Toby, that truancy often develops after an official absence of some sort. It may be of note that the university is reserving a week each term in the coming year in which we shouldn’t plan sessions, and that might have the same effect.

I got a complaint letter last summer from a student saying Ed Studies was poor value for money because we don’t utlise the summer term/block. It is a complaint I’ve heard a few times (but not many times) over the years and was linked to a false concept that students pay for three terms but get only two terms of teaching. Whenever I’ve asked previous complainants whether they’d prefer the current hours for each module to be spread out across the three terms, or to start modules at different time to each other so some extended into the third term, the students have been very much against that. They do not want what we do spread out, they want more of what we do. The semesterisation plan seems to be based on a strategy of doing exactly what students have said they don’t want, yet those proposing and putting into place repeatedly assure us that it has been student-driven. I assume that they either ask other students, or they ask in the wrong way/the wrong questions: If Q = Do you want sessions in all three terms? A = Yes please, but if Q = Do you want to have your sessions spaced out so that you will have to come in to uni during all three terms, even though you won’t actually get any additional module sessions? A = No, definitely not.

As a post script: The complainant last summer was one of our poorest attenders, and I have no faith what so ever that s/he would have attended many (if any) of the additional sessions being requested if they had been provided.

A fascinating insight into ‘wobble week’ driven by the student voice. The triggers explored and how these may be alleviated (to an extent) provide areas of reflection into the ongoing nature of educational transition, the multi-faceted nature of this and of student engagement.