While the mentor figure might change during a learning journey (usually from teacher to peers), at the beginning of the unit it is usually the teacher (which nicely aligns with the Wise Old Man or Woman who so often delivers the Call to Adventure). It can be helpful not to identify too strongly the role of the mentor with the person of the teacher, or convey the impression that the teacher always is the mentor, and that no one else can perform this role. The teacher may not always be a mentor, and mentors may be found in many people and places (including within oneself). Ultimately, the mentor can only accompany the students for part of their journey, and eventually the students will have to stand on their own and demonstrate understanding by themselves. The teacher cannot make the students learn, and the students must accept the challenge of education themselves. Nevertheless, the mentor plays an important role in encouraging, advising, guiding and supporting their students, particularly in the early stages of their journey.

Stage iv) The hero is encouraged by the Wise Old Man or Woman (MEETING WITH THE MENTOR(S))

Diagnostic questions for stage iv):

- Who are the mentor figures that will support the students during their journey through this unit? Apart from you, who are the various mentors and allies that students will have to support them during this unit? Other students in the class? Study groups? Textbooks, the VLE and other online resources? Other members of academic staff? Technical staff? Library staff? Learning developers/academic support staff? Learning technologists? Student support advisors (including additional support for students with learning difficulties, wellbeing and mental health support, financial support, etc)? (Think about all the things at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy that need to be in place in order for a student to be in a position where they can learn.)

- What can they reasonably expect from you, their teacher? And how can you manage their expectations? Can they email you? If so, what is your usual response time? Is there a unit FAQ discussion board they can post to? If so, can students both answer and ask questions? Do you have office hours they can turn up for? (In terms of managing expectations, what the particular answers to these questions are is less important than students knowing what the answers are.)

- How can you avoid being overwhelmed by out of class requests for support? How can you create a learning environment in which students are less dependent on you? What can you do to encourage students to develop autonomy and self-confidence in their ability to help and support themselves? Do you need to spend time looking at or linking to resources that will help students improve their self-efficacy?

- Do you plan to be the students’ mentor throughout the unit, or will you change role later on (e.g. trickster*)? Or will you change role depending on the student, and what they can cope with? (Perhaps a less confident student will require mentoring for longer, but a more able student may appreciate the challenges presented by a trickster teacher.)

- Are there any other mentors that might change roles? (A technology, for example, might be considered a shape-shifter – sometimes being helpful, but at other times being frustrating or even destructive.)

*See, for example: Parks, J. G. (1996) The teacher as bag lady. College Teaching, 44(4), or; Davis, K. W. and Weeden, S. R. (2009) Teacher as trickster on the learner’s journey. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(2).

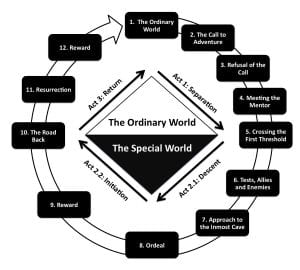

The ‘student experience’ and the ‘student journey’ are at the forefront of contemporary Higher Education, which is much more seen as an individually transformational endeavour than the simple collection of knowledge it once was. In this context it has become more and more important to consider the role and agency of students as part of learning and teaching planning, rather than just focus on content that is to be mysteriously transmitted. We suggest that it is worth considering the framework provided by the hero’s journey, a model coming out of scriptwriting, as a guiding principle behind planning new and reflecting on old learning and teaching design. In so doing, educators can provide a fresh look at their courses and modules and truly put the individual student front and centre of their own learning journey, by casting them in the role of hero. The somewhat simple formula of the hero who encounters many obstacles on their journey, and returns to the ordinary world transformed, and often with some kind of magical boon, can easily be read as the student who encounters many obstacles and tests on their journey through university (but more specifically through subject knowledge/content/skills), and (hopefully) returns to the ordinary world (or the ‘real world’ outside of the realm of academia) transformed, with the ‘magical’ boon of subject knowledge and relevant skills to their chosen discipline.

The ‘student experience’ and the ‘student journey’ are at the forefront of contemporary Higher Education, which is much more seen as an individually transformational endeavour than the simple collection of knowledge it once was. In this context it has become more and more important to consider the role and agency of students as part of learning and teaching planning, rather than just focus on content that is to be mysteriously transmitted. We suggest that it is worth considering the framework provided by the hero’s journey, a model coming out of scriptwriting, as a guiding principle behind planning new and reflecting on old learning and teaching design. In so doing, educators can provide a fresh look at their courses and modules and truly put the individual student front and centre of their own learning journey, by casting them in the role of hero. The somewhat simple formula of the hero who encounters many obstacles on their journey, and returns to the ordinary world transformed, and often with some kind of magical boon, can easily be read as the student who encounters many obstacles and tests on their journey through university (but more specifically through subject knowledge/content/skills), and (hopefully) returns to the ordinary world (or the ‘real world’ outside of the realm of academia) transformed, with the ‘magical’ boon of subject knowledge and relevant skills to their chosen discipline.